What you need to know

Many Americans say they would prefer to vote for candidates with centrist (moderate) preferences. Yet very few Republican and Democratic candidates for Congress run for office on moderate campaign platforms or behave as moderates in office. Why don’t more candidates respond to the public’s demands for moderate issue positions?

- Many Americans say they want more moderate elected officials, but there are very few moderates in Congress. Why is that?

Ideology in Congress

Analysis by political scientists reveals that most Democratic elected officials tend to hold liberal positions on issues, while Republicans generally hold conservative positions. There is variation within each party. Some Democrats are more liberal than other Democrats, and some Republicans are more conservative than other Republicans. However, few candidates from either party run on moderate platforms or behave that way in office.

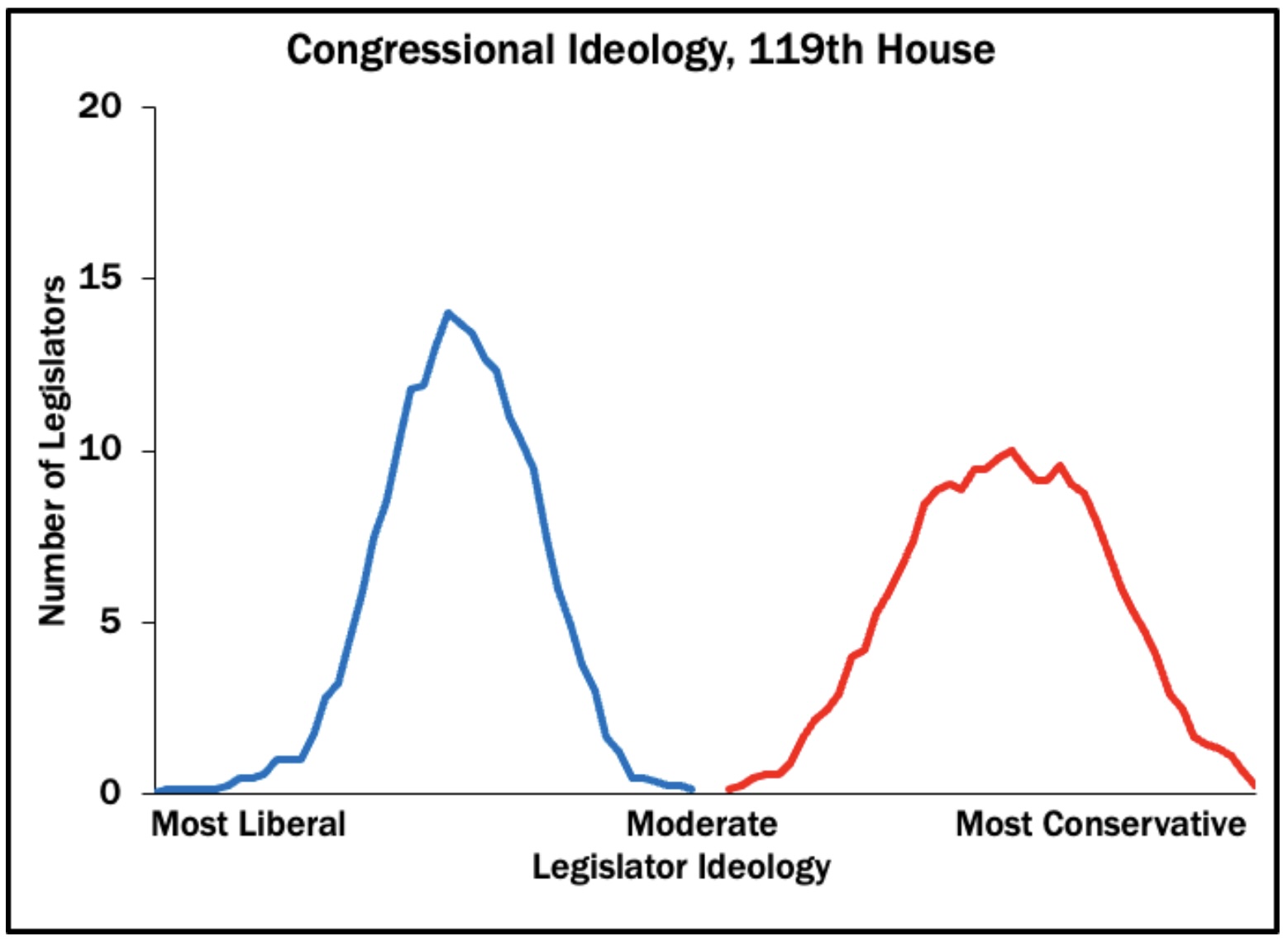

One way to show this finding is NOMINATE, a technique that estimates an elected official’s issue positions based on their voting behavior. The chart below shows the ideologies of Democratic and Republican members of the current (119th) House of Representatives.

The chart illustrates that Democrats are positioned on the left (liberal) side of the ideological spectrum, while Republicans are positioned on the right (conservative). There are very few legislators in the middle or moderate portion of the spectrum. (NOMINATE scores are relative measures, so the ends of the line are not the most liberal or conservative someone can be; they are just the most extreme members of the current Congress.)

The Median Voter Theorem

For political scientists, the absence of moderate legislators contradicts one of the most fundamental findings in voting theory, the Median Voter Theorem (MVT). The MVT states that in an election, candidates face strong pressures to select campaign platforms that match the demands of the median voter in their constituency. A 5-voter example is shown below.

Each voter’s position (ideal point) on the line describes the campaign platform they like the most. Voters choose the candidate whose platform is closest to their ideal point.

In this example, the candidate whose campaign platform is closest to the median voter (3) would likely always win regardless of where their opponent’s platform is located. Therefore, if both candidates want to win the election, they will both move their platforms closer to the median voter – in the extreme, they will both run on identical platforms that match the median voter’s ideal point.

The problem is, the MVT’s predictions do not match reality. Instead of a Congress dominated by moderates, virtually all legislators are liberal or conservative to some degree. Something else is driving members to ideological extremes.

Why are there so few moderate members of Congress?

The lack of moderates in Congress is due to several factors, but the most significant reason is the way candidates for office are selected. Both parties choose their congressional nominees through primary elections, contests held six to twelve months before the general election in November. Only citizens who are registered as party members are eligible to vote in primaries – they register for a party at the same time they register to vote.

In modern American politics, the Democratic and Republican party coalitions (the set of people who are registered with each party) are very different. Democratic party members are generally liberal or moderate, and Republicans are generally moderate or conservative. However, the median Democratic Party member is a liberal, and the median Republican Party member is a conservative.

Primary elections have a strong impact on candidates’ issue calculations. Even if candidates for office want to be moderates, they are often forced to take more extreme positions to win primary elections, which they need to do to secure a spot on the general election ballot. The result is elections where most candidates run on relatively extreme platforms, and a Congress where there are only a few moderates.

The primary system was created to give citizens greater power to determine the choices they face in general elections – and to take this power away from party leaders. However, due to the composition of current party coalitions, this system creates strong incentives for legislators to move away from the political center.

The Takeaway

The best explanation for the scarcity of moderates in Congress is that members often adopt extreme issue positions to win primary elections.

The primary system is an example of how addressing one problem (giving citizens the power to determine general election nominees) can create other problems (fewer moderates in Congress)

Additional reforms, such as California’s “jungle primary,” where candidates from both parties compete in a single primary election, have not solved the problem created by primary elections.

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

Gage, B. (2019). The Political ‘Center’ Isn’t Gone — Just Disputed. New York Times, February 7, 2019. Available at https://tinyurl.com/h8zbnbj3.

Romer, T. and H. Rosenthal. (1979). The Elusive Median Voter. Journal of Public Economics 12(2): 143-170.

Sources

Abramowitz, A.I. (2010). The Disappearing Center: Engaged Citizens, Polarization, and American Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jones, M.I, A.D. Sirianni, and F. Fu. (2022). Polarization, Abstention, and the Median Voter Theorem. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (Nature) 9(1): 1-12.

Lewis, Jeffrey B., Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet (2025). Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database. https://voteview.com/, accessed 9/1/25

West, E.A. and S. Iyengar. (2022). Partisanship as a Social Identity: Implications for Polarization. Political Behavior 44(2): 807-838.

Woon, J. (2018). Primaries and Candidate Polarization. The American Political Science Review 112(4): 826-843.

Contributors

Robert Holahan (Content Lead) is Associate Professor of Political Science at Binghamton University (SUNY). He holds a PhD in Political Science from Indiana University, where his advisor was Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom. His research focuses on natural resource policy, particularly in domestic oil and gas production, but also extends into international environmental policy. He was PI on a National Science Foundation grant that utilized a 3000-person mail-based survey, several internet-based surveys, and a series of laboratory economics experiments to understand better Americans’ perspectives on energy production issues like oil drilling and wind farm development.

William Bianco is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University and Founding Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop. He received his PhD from the University of Rochester. His teaching focuses on first-year students and the Introduction to American Government class, emphasizing quantitative literacy. He is the co-author of American Politics Today, an introductory textbook published by W. W. Norton, now in its 8th edition, and has authored a second textbook, American Politics: Strategy and Choice. His research program is on American politics, including Trust: Representatives and Constituents and numerous articles. He was also the PI or Co-PI for seven National Science Foundation grants and a current grant from the Russell Sage Foundation on the sources of inequalities in federal COVID assistance programs. His op-eds have been published in The Washington Post, The Indianapolis Star, Newsday, and other prominent venues.