What you need to know

Gerrymandering is a term derived from the name of the Founding Father and 5th U.S. Vice President, Elbridge Gerry. It is the process of drawing legislative districts in ways that benefit one political party or group of candidates over another.

- Redistricting is controlled by state governments.

- Gerrymandering typically takes the form of “cracking” and “packing” groups of voters.

- Decisions about gerrymandering shape the partisan and demographic makeup of the House of Representatives as well as state legislatures.

What is gerrymandering?

The Constitution requires congressional districts to be based on population counts. After each U.S. Census, districts are redrawn to reflect shifts in where people live. Redistricting happens at the state level, and states use different criteria: preserving county lines, ensuring contiguity and compactness, and/or avoiding incumbent clashes. In fact, states can redraw district lines at any time, not just after a Census.

Most states allow legislatures to redistrict, although some use independent commissions. As of 2025, nine states use independent commissions, and an additional ten states ban drawing maps that favor one party over another.

The partisan makeup of a district can have a large effect on which party’s candidate wins the district. As a result, the group controlling the redistricting process can produce maps that favor one party. Gerrymanders may also favor the reelection of incumbents or reduce the number of seats won by candidates who represent certain subsets of constituents. Two common tactics are:

- Cracking: Splitting up a group of voters across multiple districts to reduce their power.

- Packing: Concentrating as many like-minded voters as possible into a small number of districts.

Partisan gerrymandering often reduces competition. When districts are safe for one party, candidates are less accountable to voters, and turnout often declines. In 2024, researchers at Duke University estimated that ending gerrymandering could create 37 to 42 more competitive House of Representatives seats in U.S. federal elections, out of the 435 voting seats that are up for election every two years (both in presidential election years and in midterms).

One way to measure gerrymandering is through the efficiency gap, which captures the number of “wasted votes” each party has (votes for losing candidates plus surplus votes for winning candidates). A larger efficiency gap signals potential gerrymandering, although geographic clustering (such as Democrats in cities and Republicans in rural areas) can also produce gaps without intentional bias.

Maps drawn by nonpartisan commissions tend to have smaller efficiency gaps and more competitive elections compared to maps drawn by legislatures. We plan to focus on both non-partisan redistricting commissions and the efficiency gap in a future brief.

How does gerrymandering work?

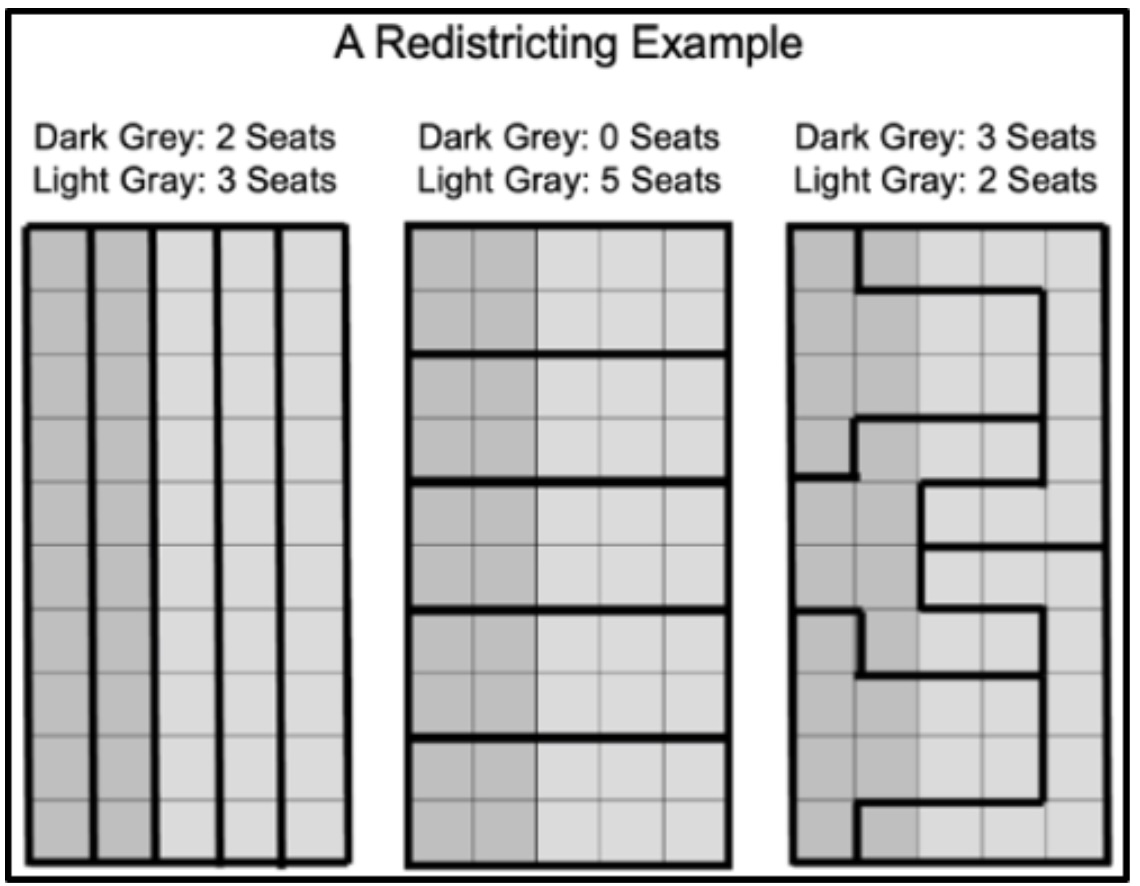

Imagine a state where 60% of voters belong to one party (light gray) and 40% to the other (dark gray). The state elects five representatives:

If district lines run north to south (the left diagram), representation reflects the population split (3–2).

If supporters of the majority party are cracked (the middle diagram), the majority wins all five districts with 60% support.

If voters from the majority party are packed (as shown in the right diagram), the majority is confined to two districts, and the minority wins three seats with 40% support.

These scenarios illustrate how cracking and packing alter outcomes, even with the same voter distribution.

What has the Supreme Court said about gerrymandering?

Modern redistricting standards trace back to the Supreme Court decision Baker v. Carr (1962), which established the principle of “one person, one vote.” The Voting Rights Act of 1965 ensured the ability to vote regardless of race or language, creating the conditions for racial gerrymanders that created districts designed to elect Black representatives. More recent rulings have limited racial gerrymanders. The Supreme Court has declined to intervene on partisan gerrymandering, most recently in Gill v. Whitford (2013). Finally, in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015), the Supreme Court upheld the use of non-partisan commissions.

The Takeaway

Gerrymandering can alter national policy outcomes by influencing who is elected to Congress.

Nine states use nonpartisan commissions to draw district lines, and nineteen states have banned maps that favor one party over another. In the remaining states, there are no limits on how lines are drawn, aside from the requirement that the districts have similar populations.

The Supreme Court has declined to intervene in cases of partisan gerrymandering. Historically, the Court has approved gerrymanders designed to increase Black representation, although recent decisions have struck down several racial gerrymanders.

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

Library of Congress. (2024). Gerrymandering: The origin story. https://tinyurl.com/4kwrusej, accessed 9/4/2025.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2024). Redistricting and census. https://tinyurl.com/3cp5y5ha, accessed 9/4/2025.

Brennan Center for Justice. (2025). Gerrymandering explained. https://tinyurl.com/475re5vx, accessed 9/4/2025.

Sources

Duke Quantifying Gerrymandering Project. (2024). Quantifying Gerrymandering Project. https://tinyurl.com/yj7dd8sm, accessed 9/4/2025.

WUNC. (2025). North Carolina gerrymandering case led to redistricting battle in Texas, and perhaps beyond. https://tinyurl.com/4m9pdrz8, accessed 9/4/2025.

Washington Post. (2014). The remarkable recent decline of split-ticket voting. https://tinyurl.com/4vr2kanh, accessed 9/4/2025.

Spencer, D. (2023) Who draws the lines? All About Redistricting. http://tinyurl.com/4pvb7xk8, accessed 2/21/24.

Contributors

Lindsey Cormack (Content Lead) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Stevens Institute of Technology and the Director of the Diplomacy Lab. She received her PhD from New York University. Her research explores congressional communication, civic education, and electoral systems. Lindsey is the creator of DCInbox, a comprehensive digital archive of Congress-to-constituent e-newsletters, and the author of How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It’s Up to You to Do It) and Congress and U.S. Veterans: From the GI Bill to the VA Crisis. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Bloomberg Businessweek, Big Think, and more. With a drive for connecting academic insights to real-world challenges, she collaborates with schools, communities, and parent groups to enhance civic participation and understanding.

William Bianco (Research Director) is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University and Founding Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop. He received his PhD from the University of Rochester. His teaching focuses on first-year students and the Introduction to American Government class, emphasizing quantitative literacy. He is the co-author of American Politics Today, an introductory textbook published by W. W. Norton, now in its 8th edition, and authored a second textbook, American Politics: Strategy and Choice. His research program is on American politics, including Trust: Representatives and Constituents and numerous articles. He was also the PI or Co-PI for seven National Science Foundation grants and a current grant from the Russell Sage Foundation on the sources of inequalities in federal COVID assistance programs. His op-eds have been published in The Washington Post, Indianapolis Star, Newsday, and other venues.