What you need to know

As of 12:01 a.m. on October 1st, 2025, the federal government is in a shutdown. Shutdowns are rare in other democracies but have become more common (and longer) in the U.S. A shutdown halts many government activities and stops pay for federal workers, creating a sense of disorder for American citizens and businesses. In this brief, we will:

- Explain what triggers a shutdown.

- Spell out what keeps running (and what doesn’t) during a shutdown.

- Discuss how often shutdowns have occurred, how much they cost, how they begin, and how they end.

What is a government shutdown?

The Antideficiency Act bans agencies from committing or spending money they don’t have. A shutdown occurs when Congress fails to enact the 12 annual appropriations bills or a stopgap continuing resolution (CR) by the end of the fiscal year, leaving agencies with no authority to spend money. The fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30. If Congress doesn’t enact a spending bill by the end of the fiscal year, all “non-excepted” or “non-essential” government operations come to a halt until funding resumes.

How many times have we had government shutdowns?

Since 1976, when Congress adopted the modern budget process, there have been about 20 funding gaps lasting a full day. Over the past 30 years, there have been five shutdowns that have lasted more than one business day. These were in 1995-96 (twice, for 5 and 21 days), 2013 (16 days), 2018 (3 days), and 2018-19 (35 days).

What stops during a government shutdown?

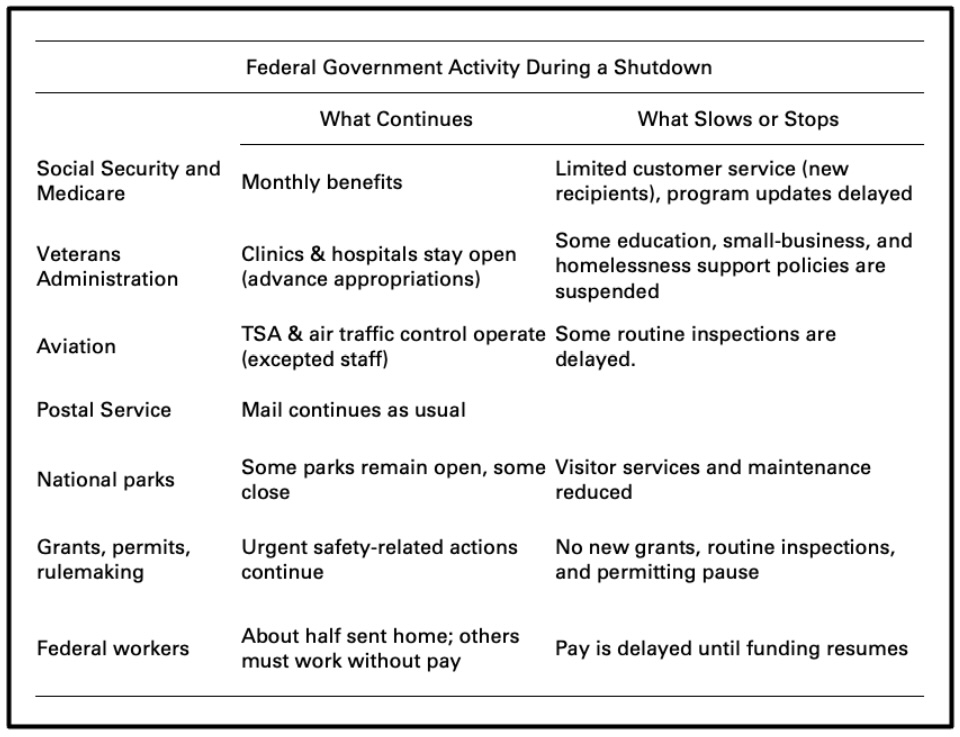

Operations of the government deemed “essential” are exempt from shutdowns. These are activities that protect life and property or are otherwise authorized by permanent law (e.g., air traffic control). Non-exempt workers (about half of the civilian federal workforce) are sent home without pay. Employees in essential roles, such as those in the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), are required to report to work. Both receive back pay after funding resumes. Here are some examples of what continues and doesn’t continue during a shutdown.

In past shutdowns, all federal workers have returned to their jobs after a shutdown. The situation might be different in 2025. On September 25, 2025, the Office of Management and Budget instructed agencies to prepare Reduction-in-Force (RIF) plans in the event of an extended shutdown. This directive goes beyond routine furlough planning and may result in significant reductions in the federal workforce. Any RIF is certain to be appealed to the federal courts, which may reverse the action.

How costly are shutdowns?

During the longest 35-day shutdown of 2018–19, the Congressional Budget Office estimated a $11 billion reduction in GDP, with $3 billion in losses that the economy never recovered from. It also delayed about $18 billion in discretionary federal spending. Longer lapses could create private-sector delays in hiring, investment, loans, and certifications.

One of the reasons shutdowns are expensive is the stop-and-start nature of abrupt endings. Agencies lose time reauthorizing systems, renegotiating contracts, rescheduling lab work, and clearing backlogs for tasks such as maintenance or inspections.

Why do shutdowns happen, and what are members of Congress disagreeing over this time?

Shutdowns generally involve partisan disputes over total government spending or specific policy demands that involve spending cuts or additions.

In 2025, the Republican Party holds the majority in the House. Bills in the House only require a majority to pass. The Republican Party also holds a majority in the Senate, but due to the possibility of a filibuster, passage requires 60 votes. The House passed a continuing resolution on September 19, 2025. When the Senate considered the measure, it failed on a 44-48 vote.

Senate Democrats want the CR to include an extension of the Enhanced Premium Tax Credits, which are Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies that lower the cost of insurance for low-income individuals. These subsidies, which currently cost about $30 billion per year, were enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic and are set to expire at the end of this year. If the credits lapse, ACA premiums will increase, and an estimated four million people will choose to end insurance coverage. The enhanced credits weren’t included in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) earlier in the year. Republicans used the budget reconciliation procedure to pass OBBBA, which meant no Democratic votes were necessary for passage.

How do shutdowns end?

Shutdowns end when Congress enacts a spending bill that covers the unfunded accounts either through a CR or full-year appropriations, and the President signs it.

The Takeaway

Shutdowns occur when Republicans and Democrats cannot reach an agreement on spending levels, and neither party has enough votes to enact a budget on its own.

Past shutdowns have disrupted government operations but have had a minimal impact on the overall economy.

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

Congressional Research Service. (2025). Government Shutdowns and Executive Branch Operations: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). https://tinyurl.com/2p9pfcmr, accessed 9/26/25.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2025). Government Shutdowns Q&A: Everything You Should Know. https://tinyurl.com/ehn7azfr, accessed 9/26/25.

Dykema, M. & Wallace, M. (2023). What a Government Shutdown Would Mean for Local Governments. National League of Cities. https://tinyurl.com/yc7phxkb, accessed 9/26/25.

Sources

United States Senate. (2025). Roll Call Vote 119th Congress - 1st Session. https://tinyurl.com/3n6ws2xm, accessed 9/26/25.

O’Dell, H. (2023). Do Other Countries Have Government Shutdowns? - So Why are They More Common in the US?? The Chicago Council on Global Affairs. https://tinyurl.com/3axrp8pf, accessed 9/26/25.

Wessel, D. (2024). Government Shutdowns: Causes and Effects. Brooklings. https://tinyurl.com/4658zdec, accessed 9/26/25.

Ahn, Y. & Lee, E. & Resh, W., & Wang, W. (2023). The Effect of the 2018-2019 United States Government Shutdown on Federal Workforce Turnover. https://tinyurl.com/2p9wsnez, accessed 9/26/25.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2025). Shutdowns/Lapses in Appropriations. https://tinyurl.com/8p8ddbzn, accessed 9/26/25.

Murray, J. & Wilson, C. (2024). Past Government Shutdowns: Key Resources. https://tinyurl.com/yjn8zjwu, accessed 9/26/25.

Congressional Budget Office. (2019). The Effects of the Partial Shutdown Ending in January 2019. https://tinyurl.com/2xfxp9j6, accessed 9/26/25.

Congress.Gov. (2019). Government Employee Fair Treatment Act of 2019. https://tinyurl.com/249926f8, accessed, 9/26/25.

West, A. (2025). House Passes Continuing Resolution; Senate Continues to Weaken filibuster. GovTrack. https://tinyurl.com/ezx7b3mc, accessed 9/26/25.

Sullivan, J. & Rapfogel, N. (2025). Five Key Changes to ACA Marketplaces Amid Uncertainty Over Premium Tax Credit Enhancements. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://tinyurl.com/3yyp9uxb, accessed 9/26/25.

Contributors

Lindsey Cormack (Content Lead) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Stevens Institute of Technology and the Director of the Diplomacy Lab. She received her PhD from New York University. Her research explores congressional communication, civic education, and electoral systems. Lindsey is the creator of DCInbox, a comprehensive digital archive of Congress-to-constituent e-newsletters, and the author of How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It’s Up to You to Do It) and Congress and U.S. Veterans: From the GI Bill to the VA Crisis. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Bloomberg Businessweek, Big Think, and more. With a drive for connecting academic insights to real-world challenges, she collaborates with schools, communities, and parent groups to enhance civic participation and understanding.

William Bianco (Research Director) is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University and Founding Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop. He received his PhD from the University of Rochester. His teaching focuses on first-year students and the Introduction to American Government class, emphasizing quantitative literacy. He is the co-author of American Politics Today, an introductory textbook published by W. W. Norton, now in its 8th edition, and authored a second textbook, American Politics: Strategy and Choice. His research program is on American politics, including Trust: Representatives and Constituents and numerous articles. He was also the PI or Co-PI for seven National Science Foundation grants and a current grant from the Russell Sage Foundation on the sources of inequalities in federal COVID assistance programs. His op-eds have been published in The Washington Post, Indianapolis Star, Newsday, and other venues.