What you need to know

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, many Americans began to notice rising prices on everyday items, from eggs to housing costs. While inflation rates have eased in recent months, rising prices were at the top of the mind for voters in the 2024 Presidential election. What is inflation, what causes it, and what can policymakers do to counteract its negative effects?

- Inflation is one of the most commonly cited concerns for many Americans.

- What causes inflation?

- Can the federal government control inflation?

What is inflation?

Inflation occurs when the price of goods and services increases over time. As inflation rises, the same amount of money buys fewer goods and services. For example, suppose gasoline costs $3.00 per gallon in January. At this price, it costs $36.00 to fill a 12-gallon gas tank. If inflation causes gas prices to increase by 10% by December, gasoline now costs $3.30 a gallon, and the same $36.00 will buy only 11 gallons. In effect, $1.00 in December is worth less than $1.00 last January.

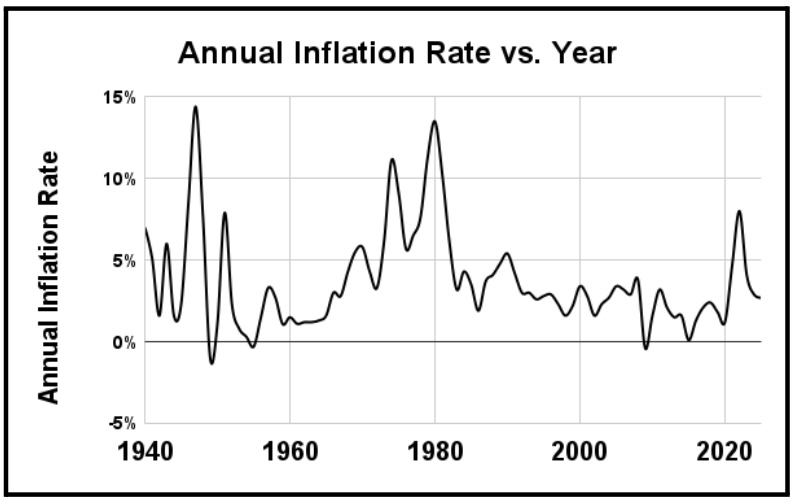

The national inflation rate is determined by checking the prices of a fixed set of goods and services over time. The figure below shows the annual inflation rate from 1940 through 2024. Over this time, the typical inflation rate has been about 2%, although there have been periods of much higher inflation. After the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation increased to an annual rate of 4.7% in 2021 and 8% in 2022, but decreased to 2.9% in 2024. The highest inflation rate since World War II occurred in the 1970s, when increased oil prices led to overall inflation rates exceeding 14%.

What causes inflation?

Inflation occurs because of two economic factors: supply and demand.

When the supply of a good or service decreases because of a shortage, the price of that good or service increases as the same number of people wanting to buy it are competing for less supply. An example of this can be seen in the egg price inflation of 2024, which was largely caused by bird flu killing a significant number of egg-laying hens.

Similarly, when demand for a good or service increases, more people compete to buy the same amount of the good or service, leading to a price increase. An example of this is in the housing market: When new people move to an area, but the pace of new home construction doesn’t keep up, it will result in more people competing for the same amount of housing inventory, and prices go up.

Why does inflation matter?

Purchasing power is the amount of goods and services that can be bought with a fixed amount of money. As inflation increases, purchasing power decreases. Inflation also affects the interest rates people pay for mortgages, car loans, and other consumer credit. High inflation also creates uncertainty, making it harder for businesses to plan expansions, and causes individual consumers to be more cautious about large purchases such as a home or a car. Both of these effects of high inflation can lower economic growth.

Low rates of inflation are not necessarily a bad thing. Most economists consider inflation rates of 2-3% to be healthy. However, negative inflation rates are thought to discourage business investment and consumer spending, leading to lower rates of economic growth.

Can inflation be controlled?

Inflation is not easily controlled, but governments can take some steps to stabilize it.

In the federal government, the primary responsibility for controlling inflation falls to the Federal Reserve Bank (abbreviated FRB, usually referred to as The Fed), which sets the interest rate at which banks borrow money from each other or the Fed. Banks then adjust their interest rates for loaning money to individuals and businesses based on this rate. When interest rates go up, it is more expensive to borrow money, so the demand for goods and services goes down (inflation decreases). When interest rates go down, it is cheaper to borrow money, so the demand for goods and services goes up (inflation increases).

The problem the Fed faces is that raising interest rates to lower inflation can also lower economic growth and even cause a recession. By law, Federal policy must balance the goals of keeping inflation low and promoting economic growth. It is hard to achieve both goals simultaneously. For example, the Fed raised interest rates in 2022 and 2023 to control inflation, accepting the risk that rate increases would slow economic growth.

Changes in federal spending enacted by Congress also affect the inflation rate. By increasing spending, Congress can cause demand-induced inflation. In the same way, reducing (or limiting increases) in spending can reduce inflation. High levels of government borrowing (to fund a budget deficit) can also cause inflation.

Locally, governments can impact inflation by enacting policies that affect the supply of certain goods, such as housing. Restrictive zoning requirements, for example, can result in a lower housing inventory than locally demanded, leading to an increase in housing prices. Similarly, recent green energy policies passed by states led to an increase in demand for the supplies needed to build wind power turbines, which increased the price of those supplies and made projects significantly more expensive.

The Takeaway

Inflation peaked in the early 2020s, but as of July 2025 has mostly returned to prior levels.

Inflation is caused by increases in demand or decreases in supply. During a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation can become higher as markets adjust to changing economic conditions.

Governments often play a role in both creating inflation and decreasing inflation, but so do free market forces like supply and demand.

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

Ihrig, J.E., K.L., Kleisen, and S.A. Wolla. (2023). The Rise (and Fall) of Inflation During the Early 2020s. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available at https://tinyurl.com/3868dtt9, accessed 6/6/25.

Labonte, M. (2023). Introduction to the U.S. Economy: Monetary Policy. Congressional Research Service. Available at https://tinyurl.com/y2692add, accessed 6/5/25.

Sources

Federal Reserve. (2025). Monetary Policy Report. Federal Reserve. Available at https://tinyurl.com/4hvu5hv9, accessed 6/6/25.

Federal Reserve. (2025). Why Does the Federal Reserve Aim for Inflation of 2 percent Over the Longer Run? Available at https://tinyurl.com/m6s3wz64, accessed 6/6/25.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. (2025). Consumer Price Index 1913-present. Available at https://tinyurl.com/r8mpb439, accessed 6/5/25.

Labonte, M., & Weinstock R. 2022. Inflation in the U.S Economy: Causes and Policy Options.

Congressional Research Service, accessed 1/23/23, available at tinyurl.com/mvjtmks9

Weinstock R, L. 2022. Back to the Future? Lessons from the “Great Inflation.” Congressional Research Service, accessed 1/27/23, available at tinyurl.com/jxuz8z7w

Binder, C., & Kamdar, R. 2022. Expected and Realized Inflation in Historical Perspective. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(3), 131–156, available at jstor.org/stable/27151257.

Salwati, N., & Wessel, D. 2021. How does the government measure inflation? Brookings Institution, accessed 2/2/23, available at tinyurl.com/53dnzvmf

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Sannikov, Y. 2016). On the Optimal Inflation Rate. The American Economic Review, 106(5), 484–489, available at jstor.org/stable/43861068

Labonte, M. 2023. The Federal Reserve and Inflation. Congressional Research Service, accessed 1/30/23, available at crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11868

Contributors

John Arnold (Intern) is a sophomore at Binghamton University majoring in Political Science and Economics.

Robert Holahan (Content Lead) is Associate Professor of Political Science at Binghamton University (SUNY). He holds a PhD in Political Science from Indiana University where his advisor was Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom. His research focuses on natural resource policy, particularly in domestic oil and gas production, but also extends into international environmental policy. He was PI on a National Science Foundation grant that utilized a 3000-person mail-based survey, several internet-based surveys, and a series of laboratory economics experiments to better understand Americans’ perspectives on energy production issues like oil drilling and wind farm development.

William Bianco is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University and Founding Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop. He received his PhD from the University of Rochester. His teaching focuses on first-year students and the Introduction to American Government class, emphasizing quantitative literacy. He is the co-author of American Politics Today, an introductory textbook published by W. W. Norton now in its 8th edition, and authored a second textbook, American Politics: Strategy and Choice. His research program is on American politics, including Trust: Representatives and Constituents and numerous articles. He was also the PI or Co-PI for seven National Science Foundation grants and a current grant from the Russell Sage Foundation on the sources of inequalities in federal COVID assistance programs. His op-eds have been published in the Washington Post, Indianapolis Star, Newsday, and other venues.

An earlier version of this policy brief was researched and written in January-February 2023 by Policy vs. Politics interns Riana Bucceri, Greta Filor, Raegan Gautam, Sarah Hanna, Jordyn Ives, Nithin Krishnan, Nick Markiewicz, Aditi Menon, Zul Norin, Rosa Nice, Eli Oaks, and Mary Stafford, with revision by Dr. William Bianco and review by Dr. Nicholas Clarke and Professor Cory Colby.