What you need to know

The U.S. House of Representatives (“House”) is comprised of 435 voting members who are elected based on the population of each state and six non-voting members who represent the District of Columbia and U.S. territories. The House, along with the Senate, forms the United States Congress and is responsible for creating federal laws. America conducts a national census every 10 years. Afterwards, House seats are reallocated to states, which then revise House and state legislative districts to account for population shifts and the addition or subtraction of House seats. Depending on whether a legislative district has more Democratic or Republican voters, reallocating seats can affect voter outcomes and, ultimately, the legislative impact that follows.

Once legislative districts are redrawn, they generally remain in place until the next Census. However, in many states, it is legal to redraw district lines between each Census. In this brief, we address common questions about mid-cycle redistricting:

- Which states are pursuing mid-cycle redistricting?

- How recent court rulings and political incentives motivate this process.

- The potential partisan consequences of mid-cycle redistricting in 2025.

What is mid-cycle redistricting?

In August 2025, the Texas state legislature approved a new congressional map that created five seats, likely improving the odds that more Republicans would be elected to office. Texas currently has 38 congressional seats, of which 26 (64.8%) are held by Republicans; the new plan could shift the balance to 31/38 (81.6%). President Trump, the Republican candidate for President in 2024, received 56.1% of the popular vote in Texas. Similar efforts designed to help elect Republicans have succeeded in Missouri and North Carolina, and are underway in Indiana and Ohio.

On the Democratic side, California voters approved a new redistricting plan in November 2025 that would likely shift five congressional seats to Democrats. California’s congressional delegation currently has 43 Democrats and 9 Republicans (82.7% Democratic) and would shift to 92.3% Democratic under the new plan. President Trump received 38.3% of the popular vote in California in 2024. Mid-cycle redistricting designed to help Democrats get elected has also been discussed in Maryland, New York, and Virginia.

Why are states doing mid-cycle redistricting?

Two major forces make off-cycle redistricting possible and palatable for legislators. First, the Supreme Court’s Rucho v. Common Cause decision (2019) precludes the ability for courts to adjudicate federal partisan-gerrymandering claims. This change, in turn, leaves room for mid-decade redistricting. Second, narrow House margins mean that both parties see one or two additional seats as a big payoff.

How gerrymandered are state delegations?

The impact of gerrymandering, or partisan-led redistricting, can be seen by calculating the partisan difference score – the difference between the share of voters who selected a Republican president and the Republican share of a state's congressional delegation to capture the partisan tilt in a state's districts (and vice versa for Democrats). In general, gerrymandered states have large partisan difference scores (positive or negative).

The chart below compares these two variables across states. The dotted line shows the hypothetical relationship between Trump's 2024 vote and state delegation when the two percentages are exactly equal. For example, if a state has 10 legislators, Trump receives 50% of the vote, and the state has 5/10 or 50% Republican legislators. (States with three or fewer representatives are omitted.)

For example, when the Republican Party’s vote share falls below 50%, their seat percentage generally lags behind the popular vote. For example, Illinois has 17 congressional seats, and Trump received 43.5% of the vote, yet the delegation has only 3 Republican House members (3/17 = 17.6%). The Republican deficit stems from the Illinois state legislature, which is majority Democratic, and the Democratic Governor enacting a redistricting plan that strongly favored Democratic candidates.

On the flip side, when Republicans have significantly more than 50% of the vote, their seat share is generally much higher. For example, Oklahoma has 5 seats; Trump received 66.2% of the vote, and Republicans hold all 5 seats. Here, a Republican state legislature and Governor enacted a gerrymandering plan that favored Republican candidates.

How much more mid-cycle redistricting can we expect?

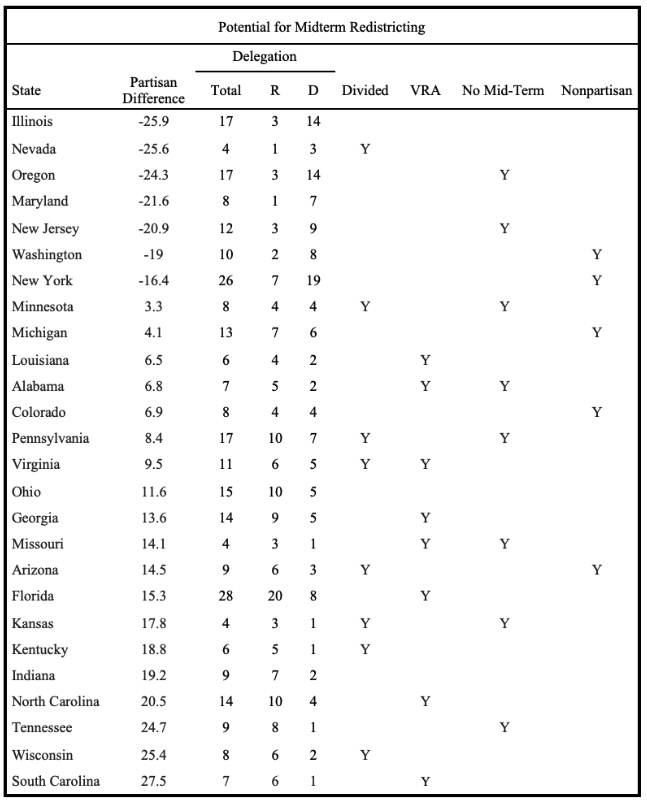

Three states have revised their maps or are holding a referendum to do so. Five other states (Connecticut, Arkansas, Iowa, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, and Utah) already have delegations that are 100% Democratic or Republican. The table below shows data on the remaining states, sorted by their partisan difference scores, along with the current composition of the state’s House delegations. The columns on the right show constraints: whether there is divided state government (no party controls both the state legislature and the governor’s office), whether the state has majority-minority districts because of the Voting Rights Act (a feature that complicates partisan redistricting efforts), whether the state Constitution bans mid-term redistricting, and whether the state uses a nonpartisan commission to redistrict.

The data in the chart suggests there is unlikely to be much additional mid-cycle redistricting in 2025. Most states face one or more of the four limitations. Only four states have no constraints: Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, and Ohio. And even in these cases, redistricting efforts can run into practical constraints. For example, Illinois’ partisan difference score shows that it is already highly gerrymandered, so it would not be easy to create additional Democratic seats.

The table also shows why partisans are focusing on states like Maryland and Indiana despite the relatively small seat gains (1 Democratic seat in Maryland and 2 Republican seats in Indiana). There are few other places to win seats through mid-cycle redistricting. The lone exception is Ohio, where Republicans could potentially pick up several seats.

The Takeaway

Mid-cycle redistricting gives parties a second chance to stretch their political advantage, testing how far they can push district lines to gain congressional seats.

Four states have already adopted mid-cycle redistricting plans, with several others in work.

Given current rules and seat shares, there is less potential for additional mid-cycle redistricting.

One wild card is a case before the Supreme Court that would remove Voting Rights Act mandates for majority-minority districts. If these restrictions are removed, several southern states would likely redistrict, shifting seats to the Republican Party. Although it is unlikely that these changes could be made in time for the 2026 midterm elections.

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

Oyez. (2019). Rucho v. Common Cause. https://tinyurl.com/y3d4yk4p, accessed 10/15/2025.

Odendahl, M. (2025). Gerrymandering mess: U.S. Supreme Court Sidestepping Partisan Question In 2019 Opens Door To Mid-Decade Redistricting. The Indiana Citizen.https://tinyurl.com/4ftmmjz4, accessed 10/15/25.

Sources

Woolley, J. & Peters, G. (2024). The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara. https://tinyurl.com/554x5vtu, accessed 10/20/25.

United States House of Representatives. (2024). Directory of Representatives. https://tinyurl.com/3s8u489m, accessed 10/20/25.

Guo, K. (2025). Texas Senate approves GOP congressional map, sending plan to Abbott’s desk. The Texas Tribune. https://tinyurl.com/uje6wcvm, accessed 10/20/25.

Kilbanoff, E. (2025). Can Texas use its new congressional map for 2026? A trio of judges will decide. The Texas Tribune. https://tinyurl.com/bdwb57dz, accessed 10/20/25.

Kuang, J. (2025). Does Prop. 50 divide California communities? Depends how you measure it. CalMatters. https://tinyurl.com/ybk4snm4, accessed 10/20/25.

Lippmann, R. & Kellogg, S. (2025). Missouri governor signs Trump-backed congressional map despite multiple lawsuits. KCUR. https://tinyurl.com/y4dkmxbz, accessed 10/20/25.

Herron, A. (2025). Vance visits amid impasse on Indiana redistricting. Axios Indianpolis. https://tinyurl.com/5byz247b, accessed 10/20/25.

Calacal, C. (2025). Missouri’s new congressional map reopens ‘old wounds’ along Troost Avenue racial divide. KCUR. https://tinyurl.com/44hrxpwp, accessed 10/20/25.

NCSL (2025) Redistrcting and Census. https://www.ncsl.org/redistricting-and-census, accessed 12/3/25.

Contributors

Lindsey Cormack (Content Lead) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Stevens Institute of Technology and the Director of the Diplomacy Lab. She received her PhD from New York University. Her research explores congressional communication, civic education, and electoral systems. Lindsey is the creator of DCInbox, a comprehensive digital archive of Congress-to-constituent e-newsletters, and the author of How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It’s Up to You to Do It) and Congress and U.S. Veterans: From the GI Bill to the VA Crisis. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Bloomberg Businessweek, Big Think, and more. With a drive for connecting academic insights to real-world challenges, she collaborates with schools, communities, and parent groups to enhance civic participation and understanding.

William Bianco (Research Director) is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University and Founding Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop. He received his PhD from the University of Rochester. His teaching focuses on first-year students and the Introduction to American Government class, emphasizing quantitative literacy. He is the co-author of American Politics Today, an introductory textbook published by W. W. Norton, now in its 8th edition, and authored a second textbook, American Politics: Strategy and Choice. His research program is on American politics, including Trust: Representatives and Constituents and numerous articles. He was also the PI or Co-PI for seven National Science Foundation grants and a current grant from the Russell Sage Foundation on the sources of inequalities in federal COVID assistance programs. His op-eds have been published in The Washington Post, Indianapolis Star, Newsday, and other venues.