What you need to know

In this brief, we explore how congressional language toward the opposing party has evolved. The analysis draws on DCInbox.com, a database of all official congressional e-newsletters to constituents, maintained by Everything Policy Content Lead, Dr. Lindsey Cormack. To do this, we:

- Analyzed every official congressional e-newsletter from the 111th–119th Congresses (2010–2025).

- Identified the words most commonly appearing near mentions of the other party for each year. This technique is known as Key Word In Context (KWIC) analysis.

- Tracked how language shifted from policy debate in earlier parts of the data to overt partisan distrust in the most recent time period.

What has changed?

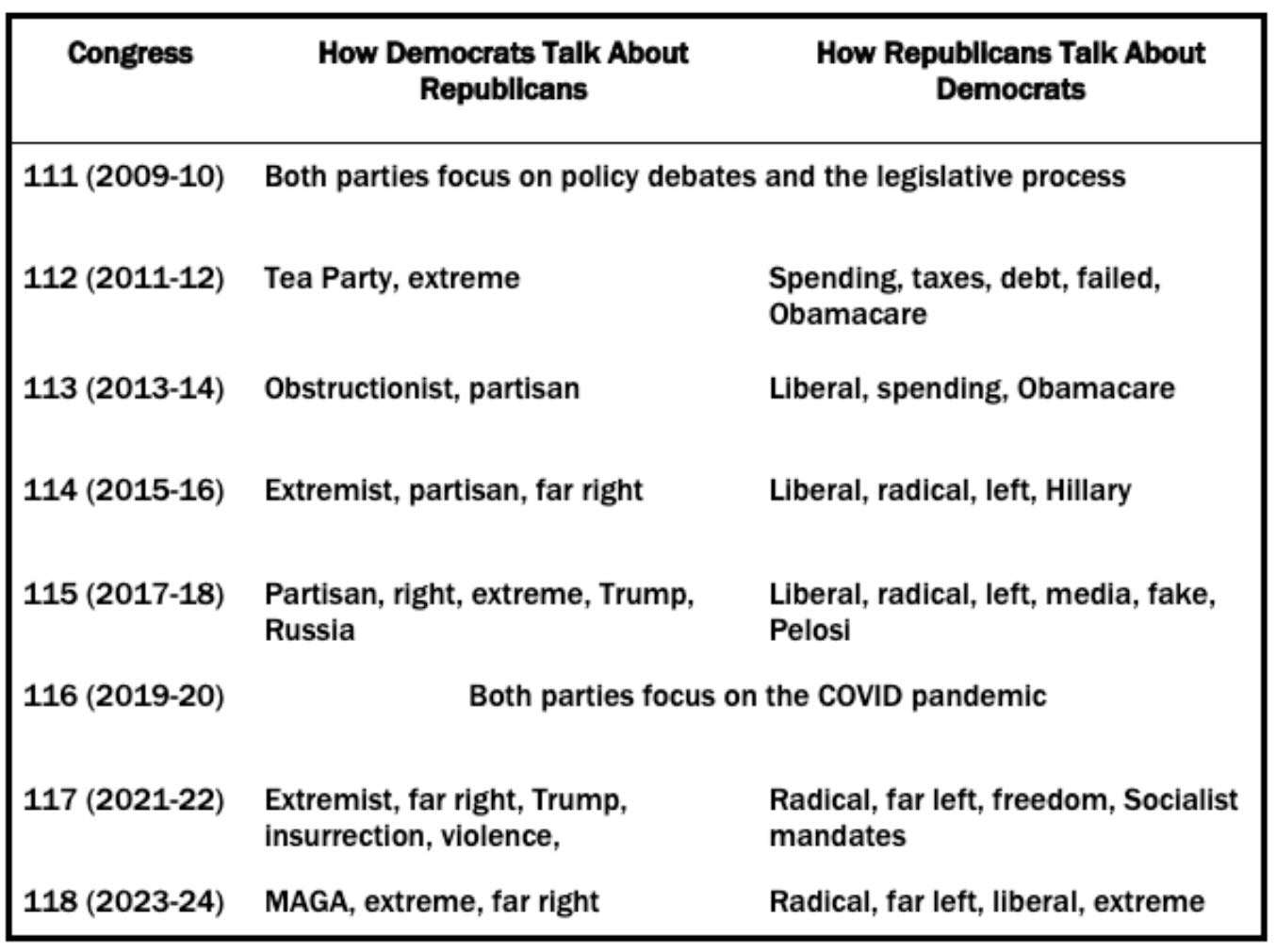

The DCInbox data collection began in 2010, during the 111th Congress (2009-2010). At that time, mentions of both parties were relatively restrained and largely policy-oriented. Legislators discussed the other party in institutional or procedural terms, with terms such as “majority,” “committee,” “legislation,” “policy,” and “vote” clustered around mentions of the other party. Anyone following politics knows this is not how things usually sound today. The table below summarizes these words and their changes over time.

In the 112th (2011–2012) Congress, the tone shifted. Republicans increasingly paired “Democrats” with words like “spending,” “tax,” “debt,” “Obamacare,” and “failed.” Both parties began using “extreme” to describe the other, though Republicans did so more often. Democrats began referencing the “Tea Party” as a faction within the GOP. By 2015, after numerous battles over healthcare, taxing and spending, and judicial appointments, Democrats described Republicans as obstructionists; Republicans continued linking Democrats with “spending” and “Obamacare.”

Additional changes occurred during the run-up to the 2016 Presidential election. Republican mentions of “Hillary” (referring to 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton) peaked that year. Democrats largely avoided using “Trump” until after President Trump took office, but since then, Republicans have mentioned “Trump” more frequently than Democrats have in each successive year.

In the 115th Congress (2017-2018), Democrats linked Republicans with “Russia” in the context of election interference investigations. Republicans, in turn, tied Democrats to “media,” “fake,” “Washington,” “liberal,” and “Pelosi” (the last refers to then-Democratic House leader Nancy Pelosi (D-CA)). The tone was increasingly combative. Democrats framed themselves as defenders of institutions and norms, while Republicans cast themselves as insurgents fighting a hostile and slow-to-respond federal government.

In the 116th Congress (2019–2020), Democrats wrote about the impeachment of Donald Trump, but the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic eventually dominated over 90% of messages sent.

The 117th Congress (2021–2022) opened in the shadow of the January 6, 2020, attack on the U.S. Capitol, which is apparent in congressional communications. Democrats associated Republicans and especially Trump with “insurrection,” “violence,” and “democracy.” As the Biden administration began, Republicans countered with “radical,” “socialist,” “mandates,” and “freedom.”

In the 118th Congress, the backdrop of the coming presidential elections was clear. Democrats started using MAGA as a shorthand for Trump Republican politics that they found distasteful, and Republicans continued to say the Democrats were too radical and their liberal policies were to blame for the current state of affairs.

In the first half of the 119th Congress, the trends of the 118th have largely persisted. Although Democrats have intensified direct attacks on President Trump, Republicans have continued to outpace Democrats in messaging, with more Republicans praising President Trump and his actions than Democrats seeking to convey negative messages. Both call the other side extreme.

What can the medium of official e-newsletters tell us about polarization?

Over time, members’ language about the other party shifted from defining specific policy differences to describing the other side as an existential threat. Before 2010, the typical newsletter focused on informing constituents of what their representative was doing on their behalf. Now, a substantial number of legislators are using newsletters to attack members of the opposing party.

It is important to note that newsletters aren’t supposed to be campaign ads. They are official government communications paid for by taxpayers. Members of Congress are explicitly prohibited from using them to solicit votes or money. Yet over time, some of these newsletters have come to mirror the language of nationalized outrage. What began as an effort to connect lawmakers with their districts has become more of a tool for some policymakers to reinforce their partisan identity.

The Takeaway

Over the past fifteen years, members of Congress have changed the way they talk about the opposing party, shifting from a focus on policy differences to blanket characterizations such as “extreme,” “radical,” “far left,” and “far right.”

It’s important to remember that only about a third of the members (roughly evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans) make these arguments. The majority of communications are about in-district issues and federal legislation. Nevertheless, these strong statements dominate media coverage of congressional proceedings, adversely affect many constituents’ willingness to consider multiple points of view, and have the potential to influence societal behavior, including increased polarization and violence in the U.S.

What congressional scholars do not fully know is whether legislators are responding to pressures from their supporters or acting as opinion leaders, shaping constituents' perceptions through the messages they send.

We also do not know the full extent of how this rhetoric translates into an unwillingness to engage in bipartisan bargaining and compromise.

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

Cormack, L. (2024). I’ve been studying congressional emails to constituents for 15 years – and found these 4 trends after scanning 185,222 of them. https://tinyurl.com/ms3mm4nf, accessed 10/6/25.

Blum, R., Cormack, L., & Shoub, K. (2023). Conditional Congressional communication: how elite speech varies across medium. Political Science Research and Methods, 11(2), 394-401. https://tinyurl.com/373tt66c, accessed 10/6/25.

Sources

DCinbox (2025).Official e-newsletters from every member of Congress. In one place. In real time. https://www.dcinbox.com/, accessed 1/20/26

Cormack, L. (2017). DCinbox—Capturing every congressional constituent e-newsletter from 2009 onwards. The Legislative Scholar, 2, 27–34. https://tinyurl.com/2m4nunjh, accessed 10/6/25.

Cormack, L. (2016). Extremity in Congress: Communications versus Votes. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 41(3), 575-603. https://tinyurl.com/rfej5nrc, accessed 10/6/25.

Luhn, H. P. (1960). Key word‐in‐context index for technical literature (kwic index). American Documentation, 11(4), 288-295. https://tinyurl.com/nwup2rry accessed 10/30/25.

Contributors

Lindsey Cormack (Content Lead) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Stevens Institute of Technology and the Director of the Diplomacy Lab. She received her PhD from New York University. Her research explores congressional communication, civic education, and electoral systems. Lindsey is the creator of DCInbox, a comprehensive digital archive of Congress-to-constituent e-newsletters, and the author of How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It’s Up to You to Do It) and Congress and U.S. Veterans: From the GI Bill to the VA Crisis. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Bloomberg Businessweek, Big Think, and more. With a drive for connecting academic insights to real-world challenges, she collaborates with schools, communities, and parent groups to enhance civic participation and understanding.

William Bianco (Research Director) is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University and Founding Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop. He received his PhD from the University of Rochester. His teaching focuses on first-year students and the Introduction to American Government class, emphasizing quantitative literacy. He is the co-author of American Politics Today, an introductory textbook published by W. W. Norton, now in its 8th edition, and authored a second textbook, American Politics: Strategy and Choice. His research program is on American politics, including Trust: Representatives and Constituents and numerous articles. and a current grant from the Russell Sage Foundation on the sources of inequalities in federal COVID assistance programs. His op-eds have been published in the Washington Post, the Indianapolis Star, Newsday, and other venues.